Artist

IMAGES: To download, click above. Credit to Jo Harvey Allen.

LINKS:

Website

Paradise Of Bachelors

Bandcamp

Instagram

Facebook

Smokin the Dummy

Paradise of Bachelors

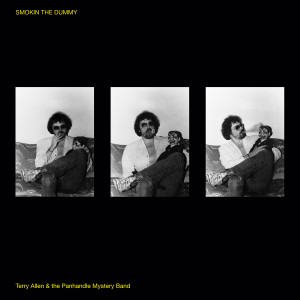

SMOKIN THE DUMMY

PISS IN THE WIND

AMERICAN MUSIC

PLAY IT AGAIN

- Terry Allen, in a 1981 letter to H.C. Westermann

Following the 1973 Whitney Biennial, in which songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen and fellow iconic artist Horace Clifford “Cliff” Westermann both exhibited, Allen maintained a lively long-distance correspondence and exchange of artworks and music with Westermann, whose singular and highly influential art he admired enormously. In a February 1981 letter to his friend and mentor, written shortly after the late 1980 release of his third album Smokin the Dummy, while he and his family were living in Fresno, California, Terry explains the genesis of the album title:

MY KID BUKKA GOT A CHARLIE MCCARTHY DOLL FOR CHRISTMAS ONE YEAR WHEN HE MADE UP HIS MIND HE WAS GOING TO BE A VENTRILOQUIST. HE IMMEDIATELY PAINTED IT UP TO LOOK LIKE A VAMPIRE … AND I JUST AS IMMEDIATELY PUT ON A PAIR OF JO HARVEY’S SUNGLASSES AND THE SLEAZIEST JACKET I COULD FIND (western slime) AND SAT FOR FAMILY PHOTOS … ANYWAY, I BLEW RINGS OF SMOKE ON THE DUMMY AND BUKKA SAID I WAS SMOKIN THE DUMMY.

I GUESS IT RANG SOME KIND OF DEMENTED BELL …

Westermann died shortly after receiving this letter, enclosed with a Smokin the Dummy LP, the minimalist black jacket of which Allen suggested that Cliff fold into a jaunty cardboard hat if he didn’t like the music. That response was unlikely, since Westermann loved Terry’s music, calling his debut record Juarez (1975) “the finest, most honest and heartfelt piece of music I ever heard.”

Recorded at Caldwell Studios in Allen’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas during the summer of 1980, exactly two years after his masterpiece Lubbock (on everything) (released in 1979) manifested in the same jury-rigged room, the feral follow-up is less conceptually focused but more sonically and stylistically unified than its predecessor. It’s also rougher and rowdier, wilder and more wired, and altogether more menacingly rock and roll. This was by design. The Panhandle Mystery Band had only recently coalesced during those 1978 Lubbock sessions, Lloyd Maines’s first foray into production. Through 1979, they honed their sound and tightened their arrangements with a series of periodic performances beyond Allen’s regular art-world circuit, including memorable record release concerts in Lubbock, Chicago, L.A., and Kansas City. Terry sought to harness the high-octane power of this now well-oiled collective engine to overdrive his songs into rawer and rockier off-road territory.

His first album to share top billing with the Panhandle Mystery Band, Dummy documents a ferocious new band in fully telepathic, tornado-fueled flight, refining its caliber, increasing its range, and never looking down. Alongside the stalwart Maines brothers—co-producer, guitarist, and all-rounder Lloyd, bassist Kenny, and drummer Donnie—and mainstay Richard Bowden (who here contributes not only fiddle but also mandolin, cello, and “truck noise theory,” the big-rig doppler effect of Lloyd’s steel on “Roll Truck Roll”), new addition Jesse Taylor supplies blistering lead guitar, on loan from Joe Ely (who plays harmonica here). Jesse’s kinetic blues lines and penchant for extreme volume—he was deaf in one ear from a near-fatal car accident—were instrumental in pushing these recordings into brisker tempos and tougher attitudes. Terry was feverish for several studio days, suffering from a bad flu and sweating through his clothes, which partially explains the literally febrile edge to his performances, rendered largely in a perma-growl. (By this point, he was regularly breaking piano pedals with his heavy-booted stomp.)

Like the album title itself, the songs on Smokin the Dummy ring various demented bells. The tracks rifle through Terry’s assorted obsessions—especially the potential energy and escape of the open road, elevated here to an ecstatic, prayerful pitch—and are populated by a cast of crooked characters: truckers, truck-stop waitresses, convicts, cokeheads, speed freaks, greasers, holy rollers, rodeo riders, dancehall cheaters, and sacrificial prairie dogs, sinners seeking some small reprieve, any fugitive moment of grace. In an echo of “Amarillo Highway (for Dave Hickey),” which opens Lubbock (on everything), “The Heart of California (for Lowell George),” another driving song and the first track of Dummy, is dedicated to Terry’s recently departed friend, the leader of Little Feat, who covered Allen’s “New Delhi Freight Train” before he died.

As on Lubbock, many other songs are older, culled from a decade and a half of songbooks, demos, and worktapes. Allen wrote “Red Bird,” a deceptively simple ditty that combines two longstanding fascinations—New Orleans and bird symbolism—as an art student in L.A. in 1964 and performed it on Shindig! the following year. He considered it his first “real” song worth keeping, and it rates as the personal favorite of many of his oldest friends, including Bruce Nauman. “Cocaine Cowboy,” composed in 1968, lent its title to a 1974 play by Allen’s colleague George Lewis, starring Terry’s wife and collaborator Jo Harvey and featuring his own dada-inspired costume designs, including a giant Gogolesque ambulatory nose wearing a cowboy hat. “Roll Truck Roll” and “The Night Cafe,” a diptych of automotive dramas, with counterpoint perspectives on the labor cultures of trucking and food service, both date to 1969. (During this era, Allen was a great enthusiast and denizen of diners, particularly Denny’s, and Jo Harvey wrote and performed a play called Counter Angel, based on her oral histories with truckstop waitresses.) The glowering, bruised 1975 rodeo song “Helena Montana” was inspired by his friend Dave Hickey’s fine rodeo number “Calgary Snow” and Terry’s impending participation in The Great American Rodeo exhibition at Forth Worth Art Museum the following year.

The other four songs, like the aforementioned “The Heart of California,” were of more recent vintage. One of only two covers in Allen’s catalog (the other is David Byrne’s “Buck Naked”), “Whatever Happened to Jesus (and Maybeline)?” interpolates Chuck Berry’s automotive lament within a skewed gospel song of Allen’s own devising, a characteristic imbrication of sacred and profane gestures. Allen completed the furiously frayed album closer “The Lubbock Tornado (I don’t know),” about the devastating 1970 tornado (still a painful local memory ten years later), in a hot Texas Tech practice room during the recording sessions. It takes the American vernacular tradition of disaster ballads into sinister and hilarious spaces, implicating governmental, religious, and alien conspiracies—including the Lubbock Lights—as possible meteorological motivations. In 1980, as in 2022, we can rationalize any calamity with conspiracy theories.

In other words, this is deathless American music. Play it again.