Artist

IMAGES: To download, click above. Photo credit to Aaron Mason.

LINKS:

Website

You’ve Changed Records

You’ve Changed Bandcamp

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

You've Changed

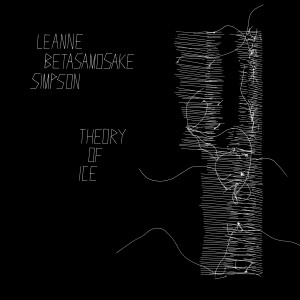

Theory of Ice is a powerful act of world-building and creative sovereignty by Michi Saagig Nishnaabeg writer, scholar, and musician Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.

One of the most compelling and important Indigenous voices of her generation, Leanne is the renowned author of Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies (named a best book of the year by the Globe and Mail); This Accident of Being Lost (winner of the MacEwan University Book of the Year; finalist for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Trillium Book Award; named a best book of the year by the Globe and Mail, the National Post, and Quill & Quire); As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (awarded Best Subsequent Book by the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association); and the creator of the album f(l)light which combined complex poetry and multi-layered stories of the land, spirit, and body with lush electronic/acoustic arrangements. This new album, Theory Of Ice is the result of an ongoing practice in the poetics and aesthetics of musical relationship, the material originating in written poetry, and worked into surprising, richly organic, song-forms through a collaborative generative process with bandmates Ansley Simpson and Nick Ferrio, producer Jonas Bonetta (Evening Hymns), and producer Jim Bryson.

“I step over watery edges…” The opening line of the album’s first track “Break Up” welcomes you into a world likely not encountered or immediately recognized by the majority of the North American settler population. Imagery circles in fragments, as water moves between forms: ice, liquid, air. We are at the intersection of states, the intersection of ways of understanding, of ways of describing, contemporary science mixing with Nishnaabeg intellectual practices. The language is precise, and surprising in its precision: “there is euphotic rising and falling / orbits of dispossession and reattachment // achieving maximum density: 39 degrees farenheit.” (Disorientation is okay. I too had to look up “euphotic”: “..of, relating to, or constituting the upper layers of a body of water into which sufficient light penetrates to permit growth of green plants” according to Merriam-Webster). Poetry often leans on metaphor for its effect, for its shocks: metaphor as an assertion of likeness, of something shared, it shocks with the newness and unexpectedness of the comparison. This type of language works because a fundamental unlikeness between the objects of the metaphor is understood, and so the distinction between objects is ultimately confirmed. The language here shocks in a different way. This language reveals relationship, embedded Nishnaabemowin appearing as both definition and poetry, a revelation of a way of thinking: “aabawe: the first warmth of spring / aabawe: a loosening of the mind / to forgive.” I hear this as a generous invitation, a reinvention of understanding, the chorus rising beautifully on a melody of “gathering” of “swimming towards light”, “thinking”, “rethinking”, and “thinking otherwise.”

Life is lived within water, we are made of water, we need clean water to live, and water exists in different states: ice, liquid, air, snow. Given a particular set of circumstances (for example where capitalism or settler-colonialism obliterates meaning, connection, and bodies) you might wish to live somewhere solid. You might want to live where you can be held, and where your hope can be held fast. In Noopiming: The Cure For White Ladies, the narrator speaks from within a frozen lake, where “there is solace in being cut off”, and “there is freedom enmeshed within that state”, asserting “being frozen in the lake is another kind of life.” Many of the songs of Theory Of Ice appear as poems in Noopiming. The album and the novel are related but distinct works, two parts of a greater project of thinking, of describing the world, of affirming a Michi Saagig Nishnaabeg existence through story and song and art. I believe “OK Indicts” is sung from this place of holding, from within this ice: “I saved shards of hope”; “I saved drops of light”. A song is a beautiful place to hold a thought, to honour a life.

Viscosity, the property, is a measure of a fluid’s internal resistance, its internal friction. “Viscosity”, the song, rides a thick groove, a reckless darkness of thick bass and drums, as it ruthlessly dissects a contemporary world that celebrates connectivity over connection, taking hard measure of the inherent friction and alienation in our social-mediated society: this “yelling the loudest in the empty room”; this “feeding fish to insecurities.” And then, after an unexpected, disrupting piano solo, rising and falling, another voice enters, and the song rises, less alone, removing itself from that world of digital violence, peeling off from the “blue light.” A remarkable change is enacted and described: building a fire, alert to the coldness of the world, and the warmth of each other, in relationship, “careful moment after careful moment.” The careful, articulate delivery of the poetry, the communal act of playing music, of singing together, of listening to each other, of trusting in each other in the creation and generation of the song – this offers a model of how worlds are generated.

“Surface Tension” arrives in a hush, Leanne dueting with John K Samson (of The Weakerthans), her friend, peer, and, through his work with Arbeiter Ring, sometimes publisher. It’s a quiet, beautiful celebration of the “simple stolen moments” and our ability “to love when we are able.” I hear the song as a gift, making those moments feel more possible, more present.

The continuity of Indigenous resistance, rebellion, and truth is reaffirmed with a powerful new arrangement by Leanne and her band of Willie Dunn’s “I Pity The Country.” Most widely known as the first track on the essential Native North America Vol 1. (Light In The Attic, 2014) compilation, the song’s ongoing relevance and resonance is a powerful indictment of the continuation and persistence of settler colonial violence in North America. The presentation here is completely contemporary and rattling in the caverns of history. It is a song filled to the highest edge with sublimated rage and a profoundly caring humanity in every word: the settler colonial state is not hated, it is pitied, for its smallness, its evil, its perpetual cruelty. I have heard this song sung at protests and marches, against the illegal occupation of unceded lands, in support of water and land protectors, by beautiful voices rallied together, united in a hope for restoration and justice. I heard Leanne and Ansley and Nick sing this song at Native North American gathering in Ottawa, in a room filled with Willie Dunn’s family and his peers, Willie Thrasher, Eric Landry, Willie Mitchell, the great poet Duke Redbird, the film-maker, musician, and force of nature Alanis Obomsawin. Immediately before Leanne’s performance news reached the auditorium that Saskatchewan farmer Gerald Stanley was acquitted by an all-white jury in the murder of Colton Boushie, the 22 year old man from Cree Red Pheasant First Nation. Screaming. Crying. Terrible silence. This is the only song I know that can hold this feeling. It’s the only song I know that’s big enough. I pity this country.

The experience of art is a powerful way of knowing, of learning; it is a gift from the world to the listener. It is an action and a way of being for the maker, it is a relationship with the world. I am thankful for the generosity of the worlds here, the life here. Life goes on in the details, and death too, a part of life. The world is amassed with details. The poet records those details as precisely as she can, singing of blankets, books, plastic flowers, pierogis, and cabbage rolls; singing of the disappearance of kids, of trailer hitches, coffee, spoons. While we were finalizing the master for the album, Leanne was definitive that it was not organized in a linear, narrative manner. It works laterally, non-hierarchically. It works musically. Yet, “Head Of The Lake” offers something like a conclusion. In the face of tragedy and in resistance to ongoing colonial violence, relationship is affirmed: “We made a circle and it helped.”; “Singing broke open hearts.” Here are Ansley and Nick, singing together, singing with Leanne, a moment of surprising beauty, understanding, and peace, and something like a conclusion, however provisional, partial, but also something like an acknowledgement of love: “in realization / we don’t exist without each other / she says: there’s nothing about you / I’m not willing to know.”