Artist

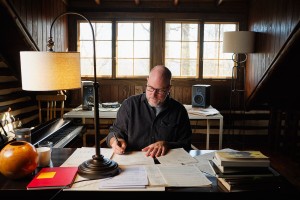

IMAGES: To download, click above. Image one credit: Brian Harnetty at Longhaven Residency, credit Poynter Photo. Image two credit: Brian Harnetty by Kevin Davison. Image three credit: Brian Harnetty with his ensemble live at Tecumseh Theater by Kevin Davison.

LINKS:

Brian Harnetty website

Brian Harnetty

Winesap Records

Over the past two decades, Columbus, Ohio, based artist and composer Brian Harnetty has been lost in sound: archives, field recordings, turntables, tape machines, radios, orchestras, toy and junk instruments, and his own chamber ensemble have all been featured in his work. At the same time, he has used the practice of listening as a way to foster social change, and as a means to understand places and people from Appalachia and the Midwest.

During these years, Harnetty developed an interdisciplinary approach to music and sound art. He brings together in-depth ethnographic research and community outreach—over long stretches of time—with the ghosts of sampled archives and his own mix of experimental, ambient, electronic, and folk music. Past and present bleed into one another to spark new music, and imagine new futures. As a result, Harnetty now moves freely between being an archivist, sonic ethnographer, composer, phonographer, writer, installation artist, community organizer, environmental activist, and myth-maker.

Words and Silences comes out of this long and varied practice, and is a sonic portrait of the Cistercian monk and writer Thomas Merton (1915-68). Harnetty edited and collaged archival recordings Merton made alone in his Kentucky hermitage in 1967 and paired them with his own newly composed music. The recordings Merton made are intimate, ranging from thoughts on Samuel Beckett, to Sufi mystics, to Michel Foucault, and notably, the 1967 race protests that took place in Louisville. Merton also managed to immediately use the tape recorder both as a contemplative tool and a medium for self-discovery. The album often feels like a one-person play—Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape comes to mind—with an exchange between Merton’s solitary voice and the ensemble’s sensitive accompaniment.

Recorded in Knoxville, Utah, Ohio, Boston, New York City, Vermont, and Berlin, Words and Silences brings together Harnetty’s ensemble of musicians to pull Merton’s voice out of the archives and into the world. The ensemble features Katie Porter Maxwell (Red Desert), Phil Rodriguez (Beirut), William Lang (Loadbang), and Jeremy Woodruff. As with his other projects, Harnetty undertook a long process of research. Harnetty began reading Merton’s books in his childhood, and starting in 2017 he began researching the hermitage audio tapes at the Thomas Merton Archives housed at Bellarmine University in Louisville.

Throughout the album there are moments of deep concentration and quiet, and always a sense of serene celebration: a fever-chill of joy. There are also subtle references to the music Merton loved throughout his life, including Louis Armstrong, Joan Baez, John Coltrane, Buck Owens, and Jimmy Smith. Brass and wind instruments evoke the attentive breathing of meditation, and the piano shares distant echoes of Merton’s love for early Kansas City Jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams.

Sometimes the music closely follows the auditory cues laid out in the tapes, as in “Breath, Water, Silence,” where Merton comments on passages of the Sufi mystic, Ibn al-‘Arabî. Here, Merton is preoccupied with breath and breathing, and this permeates each aspect of the piece. Harnetty begins with a transcribed fragment from boogie woogie piano duo Meade “Lux” Lewis and Albert Ammons. Merton’s commentary, however, seems to stretch time, so Harnetty dramatically slows the fragment down and spreads it out across several octaves. Now, greatly simplified, it expansively resonates, and helps create a pocket of space for the words to inhabit. Trombone and clarinet play long tones, the length of a breath. Along with the trumpet, the instruments color these notes with tremolos, bended notes, and buzzing sounds. Often, the music seems to reflect or comment on what Merton is saying, as when Harnetty spins out a triplet figure to correspond with the archival sounds of water dripping in a bucket and the wrens outside the hermitage. As the piece unfolds, these two elements—breath and water—wax and wane and then join together with the saxophone, which plays a melancholic, wavering three-note melody to the end.

In another piece—“A Feast of Liberation”—Merton talks of racial unrest and protests taking place that very night in Louisville, 1967. There is a striking parallel between the suffering then, and the suffering taking place now, too: the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and so many others are still raw and ringing in our ears, and once again breath has been made palpable. Harnetty adds a repeating, solitary, sparse line to Merton’s voice, built on three notes evoking John Coltrane’s Ascension (another favorite of Merton’s). It gives enough space to provide a lilting counterpoint with Merton’s voice, swelling and spinning into a cloud of dense piano lines. The music suddenly stops, and Merton’s voice returns, the words now calm and oddly quiet. It is as if he is tired and emotionally spent from the evening’s experiment, but also in a new place: the audible remnants of reflection and repose.

In all of this music, we hear Merton’s curiosity, questioning, and bewildered perplexity. We hear the tape recorder itself, acting as both a mirror and counterpart to Merton’s voice. We hear the exposed, vulnerable, uncertain self of Merton sitting alone in his hermitage. And, we hear all kinds of contradictions—between past and present, inward and outward, living and dead, time and space, everything and nothing—and we can move between them, hold them together, and listen as they melt into each other.