Artist

IMAGES: To download, click above. B&W photo credit to Milton Adams, color photo courtesy of the artist.

LINKS:

Website

Paradise Of Bachelors

Bandcamp

Instagram

Facebook

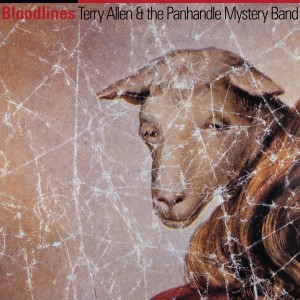

BLOODLINES

Paradise of Bachelors

I’ve never heard such a consistent assortment of unpopular styles.

– Dave Hickey, to Terry Allen, regarding his album Bloodlines, 1983

Since 1970, when they met in Allen’s studio in his hometown of Lubbock, Texas, one of songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen’s great foils and friends was the sometimes cantankerous but always brilliant art critic and writer Dave Hickey, with whom he sparred on topics musical, visual, and beyond (and to whom this reissue is dedicated in memoriam, in the wake of his passing in 2021.) Hickey, a fellow Texan paddling against the currents of the hermetic New York-centric art world, was an accomplished songwriter in his own right, and he and Terry pushed each other to refine their respective practices. In 1983, the two were thick as thieves—brothers in blood—and Hickey’s wry but big-hearted presence haunts the history and periphery of Bloodlines, the album Terry released in June of that year. Dave stood among the chorus of singers on the reprise of the title track that ends the record. Terry reprised the album cover concept, a detail of a painting of Jesus carrying a lamb that he found in the gutter outside a Lubbock botánica and manipulated, for Dave’s 1989 collection of youthful short stories, Prior Convictions—but with Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 bloody-bathtub painting “The Death of Marat” as a replacement savior. Hickey wrote the tour de force catalog essay for Allen’s 1983 solo exhibition Rooms and Stories, which featured, two months before the release of Bloodlines, the premiere of his theater piece Bleeder. Finally, there’s Hickey’s sardonic quip about the dim commercial prospects of Bloodlines. Buckets of blood and ink were spilled.

Hickey’s commercial doubts notwithstanding, critical recognition was not in short demand. In a 1984 review of Bloodlines, the L.A. Herald Examiner called Allen “one of the most compelling American songwriters working today … making the most unique art-pop of our time,” elsewhere comparing him not only to Moon Mullican and Jerry Lee Lewis, but also to the Velvet Underground and Philip Glass (probably the first time that unlikely quartet ever appeared together in one sentence). In 1983, against all odds, such sentiments were growing in underground prominence, as Allen’s records gained a fanatical word-of-mouth following—they weren’t easy to find in those days, so sometimes they existed only as a words-in-mouth—that began among fellow artists and within the rarefied air of the art world, and then, following the 1979 release of Lubbock (on everything), circulated farther afield, among musicians and fans of “outlaw country,” a loose (in all ways) subgenre and scene named in part for Hickey’s 1974 essay “In Defense of the Telecaster Cowboy Outlaws.” Allen’s early audiences included an outsized contingent of potters and bikers, due, respectively, to enthusiastic ceramicist friends and an unexpected endorsement of Smokin the Dummy (1980) in Easyriders magazine. The Rooms and Stories opening reception at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art was packed with leather-clad bikers.

On his manifold fourth album, Allen contemplates kinship—the ways sex and violence stitch and sever the ties of family, faith, and society—with skewering satire and affection alike. Bloodlines, which compiles thematically related but disparate recordings from miscellaneous sources both theatrical and historical, is itself kin to its predecessor Smokin the Dummy (chronologically and in terms of its Panhandle Mystery Band personnel and its wide-ranging subjects) and to its descendant, 1993’s The Silent Majority (Terry Allen’s Greatest Missed Hits) (which similarly anthologizes stray and orphan songs). Recorded piecemeal at Caldwell Studios in Lubbock, in sessions spanning August 1982 through January 1983, Terry self-released it, like all his previous records, on his own Fate Records imprint. Despite his frustration with the protracted timeline and some anxiety about the correspondingly higher budget, the production on Bloodlines—courtesy, once again, of master guitarist Lloyd Maines—is slicker, cleaner, and more dynamic than prior efforts, and it reached a broader audience than ever before. UK label Making Waves reissued it in 1985, facilitating semi-reliable European distribution for the first time as well as a 1986 UK tour, on which the great BJ Cole filled in for Lloyd on pedal steel.

Allen wrote two songs as themes for plays: the Pasadena idyll “Oh What a Dangerous Life” for Joan Hotchkiss’s 1982 play Bissie at the Baths and the gospel-coughing hymn “Hally Lou” for his wife and collaborator Jo Harvey Allen’s 1983 performance piece of the same name, in which she plays the titular revival preacher. Bloodlines is the first of several albums to revisit selections from Terry’s 1975 debut Juarez with full-band arrangements: a comic take on “Cantina Carlotta” that inhabits the tone-deaf tourist’s perspective of the hapless narrator, and a terrifying road-rage, burnt-rubber rendition of “There Oughta Be a Law About Sunny Southern California” featuring Jesse Taylor, in his final Panhandle Mystery Band recording, on “asphalt vendetta guitar” (Maines Brothers guitarist Cary Banks deftly handles lead guitar elsewhere). The irreverent hellfire-hitchhiker-on-highway ballad “Gimme a Ride to Heaven Boy” (featuring Joe Ely), in which Jesus steals the narrator’s car and beer for a joyride to the hereafter, remains a fan favorite. Terry wrote the final verses in a Texas Tech practice room the day they recorded it. “Manhattan Bluebird,” a surprisingly earnest (and unexpectedly moving) lament for the cultural insularity and provincialism of a New Yorker deluded by her own alleged cosmopolitanism, boasts one of Allen’s most beautiful minor-key melodies. On tour in Belfast in 1996, Allen’s tourmates feared “Ourland,” a thinly veiled satire of the IRA’s hypocrisy amid the Troubles in Northern Ireland, would incite a riot and urged him not to play it. Of course, he didn’t listen.

Lloyd Maines wept when Terry first played him the poignant eponymous ode to the arteries of ancestry and landscape, which sounds as ancient and eternal as a psalm. But that didn’t stop Lloyd from complaining about having too large a chorus on the album-closing extended version (he’s a notorious stickler for tuning and pitch). Twenty-five friends and family members packed the studio that day, including Dave Hickey, Joe and Sharon Ely, and Stubb of BBQ fame. “Bloodlines II” represents the recorded debuts of the Allens’ sons Bukka and Bale as well as Lloyd’s eight-year-old daughter Natalie Maines, later of the (Dixie) Chicks—a true testament to the power of blood. In 1998 Lucinda Williams covered it in a spookily spare version on Allen’s soundtrack for Jane Anderson’s film Baby Dance, starring Laura Dern and Stockard Channing. As the credits roll, the river runs through the mountains, under the moonlight. Hear the song.