Artist

IMAGES: To download, click above.

PHOTO CREDIT: Bill Sitzmann

The Faint

The Faint

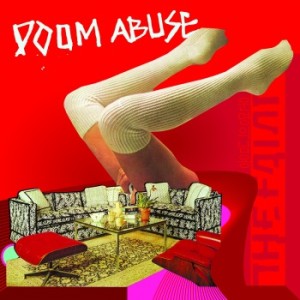

Doom Abuse

Things that don’t make sense at first often make sense later. In the creation of art, when the process is left up to the subconscious mind, when there is no preconceived concept, patterns still always emerge. Themes and recurring images, blurred in the moment, later become clear.

This is the case with The Faint’s sixth album Doom Abuse, an unexpected but also inevitable addition to their compellingly unusual catalogue of music.

To understand the album and its raw, visceral aesthetic you have to understand its birth story. You have to understand that after touring for a year on their 2008 self-released album Fasciinatiion, an album that took several years to write and produce, The Faint ceased to exist. The musicians were burned out, uninspired and could no longer find the most important element of any musical creation: fun. They went their separate ways, pursued other sorts of music in other projects, sometimes together and sometimes separately, and learned new ways of channeling sound. They remembered what drove their songwriting in the first place.

Then, in the spring of 2013, The Faint existed again. Anxious to make new music the band recorded a 4-song white label 12” they referred to as “Preversions.” That music, primal and punk rock in its approach, became the unplanned blueprint for Doom Abuse.

“The idea was ‘Let’s just book recording time and whatever we end up with is what’s going to be on this release,’” Todd says. “We wanted to make sure that the process was a fun, cathartic, expressive on instead of the laborious chore it’d started to become during the last record. The 12 inch really set the precedent for this new record.”

The band booked time with longtime collaborator Mike Mogis to mix the album before even really having songs written. There was no specific concept, just a sense of wanting to capture moments of real passion and invigorated glee. Whatever came out while writing in the band’s Omaha studio and rehearsal space would become their next album. Since much of Fasciinatiion was made sitting behind computers, the musicians wanted to embrace a live sensibility and collective rawness. A lot of the record was created live in the room, with first takes and first ideas taking precedent.

“We didn’t second guess things,” Clark says. “We just went with it. It feels more real. We wanted to see what we happened to play and just capture it. And leave the mistakes in.” “We focused a lot less on the finished product of this record than we did on the spirit of it,” Dapose adds. “The spirit was low-fi mixed with hi-fi, feedback and noise mixed with songwriting. There are some real consistencies in the songs, but it was really about a feel in general. Everything’s a lot faster on this record, it’s more rocking. It’s like a punk rock record in some ways.”

The entire album took only about three months to create. It reflects specific experiences from a specific time and sounds unlike anything else. And in its final iteration, you can see the patterns in Doom Abuse’s songs. The ideas and themes become clear. For Todd, many of the album’s lyrics were created automatically in a stream of consciousness. In the moment he didn’t know that he was centered on certain lyrical obsessions, mostly connected to the human brain and its functions.

“There’s psychic phenomenon as a theme,” Todd says. “The human animal. Different realms of communication and which ones are real and which ones are accessible. Dark places that your mind goes. I’ve been trying to find a way to give the microphone to my subconscious voice and see what it has to say. I like to sing unfiltered. See what words seem to be trying to come out and see what that is trying to say. Once you’re not listening to what your voice is saying or what your mind is spitting out, there will be words and themes there. I think that’s interesting.”

The music, too, connects. From boisterous, static-laced opener “Help In The Head” to propulsive aggressor “Evil Voices” to ambient and layered closer “Damage Control,” the album explores different variations of The Faint as a live rock band. Their history as an innovative dance act lingers, years of obsession with crafting a new style for the dance floor seeping into each song, but here and now, the band wanted to make songs that capture the sheer power and collaborative nature of their onstage performances. The songs differ and balance each other out but all share the same space and overarching tone, another pattern seen after the fact.

“Now after stepping back from it, it does feel cohesive,” Clark says. “We would finish a song and move on to the next one and never listen to it again. I remember when we got done and we listened through them to see if they made sense, it was a fun listen because the final version felt like a whole. As a set of songs it ended up related. I was surprised.”

“It encapsulates this period of time, the things we experience and encountered and our reactions to them,” Jacob says. “I think it just became cohesive naturally. Now we know what we’re doing in the studio and we know how to record so we wanted to set the situation up to create the right output. There’s mystery to something that’s not perfect – that’s why we used first takes. We didn’t want to kill any substance.”

The birth of Doom Abuse, in many ways, is in parallel with a rebirth of the band itself. The Faint, started in Omaha in the mid-‘90s, have always created against the grain, disinterested in making anything except what their own inspiration drives them to make. Each album since their 1998 debut Media has shifted and evolved that desire. Some albums, like 1999’s Blank-Wave Arcade, came from urgent, short recording processes while others, like 2004’s Wet From Birth, were more carefully constructed. The musicians themselves are the constant, together embracing a style that is truly unlike every other band out there. While Doom Abuse harkens back to Blank-Wave Arcade’s immediacy in some ways, it opens a new door. Inside is exactly where The Faint want to be now.