Artist

IMAGES: To download, click above.

PHOTO CREDIT: 1: Rough Trade 2: Dan Dennison 3: Rough Trade 4: Eva Vermandel. 5: Larry Dunstan

LINKS:

British Sea Power

Golden Chariot

British Sea Power

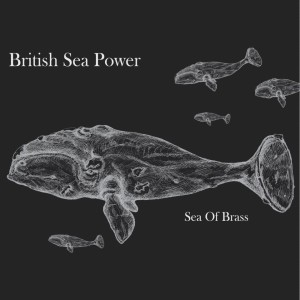

Sea of Brass

Golden Chariot Records, 10/30/15

Brass is a commonplace substance. Its names and variants are many. Nordic gold, naval brass, Muntz metal. Red brass, yellow brass, white brass, Abyssinian gold. Brass is an everyman and everywoman kind of metal, an alloy for all. It shines with a golden glow, but can be bought for pennies – a metal that can be known as both common brass and as Prince Rupert’s metal. The latter was named after a 17th-century Count Palatine for the Rhine. Prince Rupert was, apparently, something of a metallurgist and inventor. He came up with a powerful new form of gunpowder and built an early kind of machine gun. He also created his new form of brass – three parts copper, one part zinc, a touch of charcoal. And not to forget his immortal endeavour toward new means of tempering fish hooks. Among Prince Rupert’s other titles was 1st Duke of Cumberland.

The three Cumbrian members of British Sea Power are more familiar with the common metallic combo than with Prince Rupert’s magi-mix. But they, too, have turned their minds to brass. As the lyrics had it on the track True Adventures, from BSP’s 2005 album Open Season:

And what was fast is slow

And what was brass is gold

A decade after this song was recorded BSP went brass big time. The first of BSP’s Sea Of Brass concerts was at the Durham International brass-bands festival in July 2014. Arranger and conductor Peter Wraight had created a full score that would allow brass band and rock band to conjoin in beauteous union. The brass band on this occasion was the NASUWT Riverside Band, the teachers’ union band, based in the ex-mining village of Pelton Fell in County Durham and formerly known as the Newcastle Brown Ale Prize Band. This new Sea Of Brass amalgam was ready to go, but, as he prepared to conduct the first live event, Peter’s mind allowed room for another kind of metallic conjunction. “You had one oil tanker,” he says, “and you didn’t want it to collide with the other oil tanker…”

The oil tankers didn’t collide. The grinding enormity of one 500,000-ton sea monster smashing into another – perhaps the MT Hellespont Alhambra meeting the Chantiers de l’Atlantique Prarial – would be a new ultimate in avant-garde noise-wrangling. But the Durham event was something else. There was a standing ovation and some exultant reviews. Louder Than War website said the event was “completely mind-blowing… truly special.”

Brass is essentially an alloy of copper and zinc, two elements that sit side by side in the periodic table. Sea Of Brass involved less adjacent combinations. Maybe most of all, Sea Of Brass was about forging a new blend – of disparate people and objects and ideas. Indeed, it came about as a kind of industrial by-product. As BSP prepared to release their 2013 album Machineries Of Joy the band and their manager Dave Taylor looked into the the idea of playing live events in a series of machine-related sites – by the docks in Glasgow or Liverpool, at a steelworks in Sheffield and at the British Engineerium (the latter formerly the Goldstone Pumping Station in Hove in East Sussex, now an museum of engineering and steam-power). There was also the possibility of an event at a former sweets factory in Derby, now an arts venue called the Chocolate Factory. For various reasons a local connection was needed for the musical content at this venue. A little later some of BSP were flying home from Glasgow. On the aeroplane whisky was consumed and sleep and dream followed. BSP singer/guitarist Yan Scott Wilkinson imagined himself pursued by a ten-foot flying trumpet. Yan also remembered a radio documentary about brass-band competitions. An idea was born.

Yan visited the Chocolate Factory with Dave and events producer Kate Walters, who would become producer of the Sea Of Brass live events. Kate knew Peter Wraight, who also came to look at the Chocolate Factory. The initial idea was for BSP to play at the venue alongside a Midlands-based brass band, Derwent Brass. This never happened, but brass dreams were now aloft.

BSP were hardly unfamiliar with brass instrumentation. Phil Sumner’s cornet has featured with the band for nearly ten years. But full brass immersion was something new. BSP entered an unfamiliar musical realm, one where, alongside the trombone and tuba, there lurks more arcane instrumentation – the serpent, the superbone, the flupet, the helicon, the bazooka and the kangling, to name a few. The bazooka is a semi-serious brass instrument, several feet long and invented in the 1930s by the American radio comedian Bob Burns. Later the name was transferred to the anti-tank weapon. The kangling is a Himalayan trumpet often made from a human femur, and deployed in tantric chöd rituals, a subsect of Buddhist practice. Sadly perhaps, kangling and bazooka remained absent from the Sea Of Brass scheme, but there was novelty even so.

As BSP guitarist Martin Noble sees it, “Next to the complexity and ambition of the brass arrangements, our songwriting is toddler-esque.” Before creating the Sea Of Brass arrangements Peter Wraight had played or arranged brass for people including Tracey Thorn, Dizzee Rascal and Japan’s Kyoto Jazz Massive, and also on an album called Strip Joint Grooves Vol. 2. But Peter’s working life has included another metallic interlude. He spent a decade as an electrical engineer, at Rolls-Royce, working on the RB211 airliner jet engine. This fabulously intricate assemblage features titanium turbine blades forged in water-cooled copper crucibles. Peter returned to the world of music in his late twenties. Regarding his current musical activity he draws particular inspiration from Britten and Stravinsky, and he writes music for the big band he co-pilots, the Webster Wraight Ensemble. But Peter’s fathomless musical science has further dimensions. For a decade he played in the pantomime band at Nottingham Theatre Royal. There he gained insight from some of the most celebrated of contemporary artistes – the Chuckle Brothers and Cannon & Ball to name but two examples. Here, surely, was perspective that would prove useful when he came to work with BSP.

It’s interesting to hear Peter talk about the musical mechanics of BSP’s songs. He does so with a language that the band themselves can only decipher gradually: the “tetrachord note row” on Heavenly Waters, the “first inversion with a suspension” on Lately. And that’s before we get to the new musical content he added with the brass arrangements: “Superimposed quadruplets and sextuplets over the existing 12/8 pattern” in A Wooden Horse; on the song Atom “chromatically shifting diminished harmonies and melodic fragments over pedal point”. Alongside this formal terminology, Peter also deploys other key technique to ensure optimum concert performance. As Martin recalls, “Before shows Peter has a few levels of approach for tackling nerves. First a ‘safety beer’ to calm the nerves, and then a second ‘danger beer’ to really get in the mood.”

After Durham the brass shows resumed on 24 October 2014 at the De La Warr Pavilion in East Sussex. This spectacular modernist structure was built in 1935 and named after Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr. The building became a military outpost during the Second World War, its complement of troops including Royal Artillery man Spike Milligan. The Earl was a socialist and as Mayor of Bexhill he persuaded the local council to make the Pavilion a public building. Of course brass bands are open to all ideologies, but, with their strong connections with mining and industrial workforces, it’s evident that brass bands run with a certain communal spirit. A brass band can only work through unified action, the goal being communal joy not private profit. The band at Bexhill was Redbridge Brass, from the northeast London borough of the same name. Redbridge Brass have won major UK brass competitions. They’ve also played with Hot Chip at Glastonbury and appeared on BBC TV (alongside Bob Hoskins in an adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World and in a comedy slot with Joanna Lumley). In 2009 they appeared in at the Shaw Theatre in London at a production of the play Maggie’s End, marking the 25th anniversary of the miners’ strike.

Redbridge Brass, of course, has a varied instrumental population – from the cornet, the smallest and highest-pitched instrument, to the largest and lowest-pitched, the contrabass tuba. The people who make up Redbridge Brass are as diverse. There’s a neuroscientist from East London on third cornet alongside a self-described “Essex Boy” percussionist who used to play drums for Bad Manners. A principal cornet / “happy little trucker from Upminster “ features beside a flugelhorn-playing electronics engineer who designs thermal-imaging cameras. There’s a headhunter from the Kent seaside on soprano cornet beside a retired music teacher playing Eb bass. Varied players have filled their ranks. They were once home to Alison Balsom, the star of the solo trumpet who has recored a series of albums for EMI Classics. Sergeant Major Ralph Brill was the Redbridge principal cornet for several years, a man who also played with the Band of the Welsh Guards and the Band of the Scots Guards. Alan Roberts plays flugelhorn for Redbridge and also, effectively, acts as the band’s booking agent. His “gorgeous wife Fiona” plays second horn. More brass as a forum for union.

After Bexhill the next show was at London Barbican Centre – or, rather, it wasn’t. With the massed Redbridge Brass there ready on stage the show was cancelled because of power-supply failure in the area. Slightly dazed, the 1,800-strong audience traipsed off into the night, unfilled but also with that odd, humming exhilaration that sometimes comes with sudden calamity. Your correspondent has been unable to find a single serial rock-concert attendee who has experienced a similar last-minute halt to a concert – excepting, of course, one universal anomaly in the fields of general relativity and the geophysical laws, the empirical irregularity known to science as Mark E Smith. If only Mark had been on hand to help deal with the sudden no-show glut of backstage rider at the Barbican. As Yan observed: “The only real problem with the brass shows was the rider. Suddenly we found ourselves needing 600 cans of lager and eight bottle of whisky – and then all the extra booze for the brass band as well …” Ho ho.

At least, however, one member of BSP had got to play at the Barbican. Phil had been here before. In 1990, as a 15-year-old second cornet in Shropshire County Brass, he’d played at the same venue as part of brass-band competition. As the Sea Of Brass dates approached, Phil had been worried about what the brass bands would make of his own cornet sound. “I’ve spent years perfecting it,” he says, “literally years. I always thought just one dry cornet sounded rubbish live. I used to stick it through all sorts of guitar pedals, Big Muffs the lot. Two channels, three channels… I was trying to recreate a bunch of brass – at least that was the aim. In the end, though, the conductor of one of the brass band complimented me on it. I thought he was taking the piss until he said it again another night. I have my effects and they have sheet music. Even Stevens…”

Redbridge Brass seemed to take the Barbican cancellation in their stride. The knockabout humour that can be detected in the specialist world or brass jokes is perhaps testimony to a spirit of laugh-or-you’ll-cry resilience, of accord in the face of instrumental ethnic diversity. I say, I say, I say, why is a bassoon better than an oboe? The bassoon burns longer. How do you get two piccolo players to play in unison? Shoot one. The brass world is one of divergence as well as commonality. Don’t even get them started on the disputatious dimensions of embouchure, the manner in which the lips are applied to the mouthpiece. The celebrated Arban embouchure says you should have one-third of the mouthpiece on the top lip. Saint-Jacome’s own labial credo, on the other hand, demands a fight to the death in favour of two-thirds of mouthpiece. In his classic 1962 text The Art Of Brass Playing, emperor of embouchure Philip Fargas wrote that the airstream should be directed straight down the shank of the mouthpiece. But, then, in 1970, Fargas totally contradicted himself in his equally seminal work A Photographic Study of 40 Virtuoso Horn Players. All brass players are united against ‘double buzzing’, which sounds like a night out with Bez circa 1989. Unless, that is, you’re the late Greek-French architect-engineer and composer Iannis Xenakis, for whom the double buzz was a portal to a glorious expanse of split-tone futurity.

After the Barbican the other Sea Of Brass shows went ahead as scheduled. At the Sage in Gateshead BSP played again with the NASUWT Riverside Band. At Warwick Arts Centre it was the Jaguar Land Rover Brass Band, formed in 1944 in Coventry as the Air Training Corps Band. Then it was a Friday night in Kendal, hometown to half of BSP. The band were playing with Fodens Brass Band from Cheshire. It was the first ever first show in a new venue, another former manufacturing centre – a renovated carpet factory. The touring party arrived to find a spacious interior, big enough for the tour van to drive right inside. Over the PA BSP soundman Joe Hawley blasted out the theme from Benny Hill. Fabled BSP driver / guitar technician Welsh Paul spun the tour van around the venue’s interior in stop-start comedy circles. The Benny Hill theme is Yakety Sax, composed in 1963 by the US musicians James Q ‘Spider’ Rich and Homer ‘Boots’ Randolph III. The track is a forum for honking sax action, and musical purists will tell you that a saxophone is woodwind. Regardless, the instrument shines with all the lucent aureate subtlety of brass.

BSP and the Riverside Brass Band eventually played in concert at the Barbican in January 2015. Across the wide stage, rock and brass looked wonderful and odd together. On one side of the stage, we had BSP’s on-trend powder-monkey sports-casual look, exclusively supplied by Save The Children – much of this couture no doubt hand-purchased by BSP singer/bassist and style swami Hamilton, aka Neil Wilkinson. (The exception to this look, of course, being viola sensation Viola Abi, who opted instead for a nice red dress and some classic silver-screen elegance). On the other side of the stage were the smart shirts and ties of Redbridge – sat behind their scores and their attendant embroidered and tassled music-stand banners.

Suddenly, it seemed, the Trooping Of The Colour was pushed into arranged marriage with The Muppet Show – albeit with BSP rhythmaticist Matthew ‘Woody’ Wood playing down the Animal element and keeping the beat with quieter XXXXXX in place of typical rock drumsticks. BSP and the brass represented two different routes to reverb, two contrasting trails to tonality. Winds from the lungs sent down endless chicanes and bends of metallic tubing. Electricity transmitted from electromagnetic pickups to the equally labyrinthine wiring of amplifiers and speaker cabinets. But together these disparate units looked and sounded compelling.

BSP’s Yan says he was almost overwhelmed by the combined effect of this mutual music-generation society. “I remember looking around the hall,” he says, “looking at the nearly-two-thousand faces in the audience and looking at the brass band and at us lot and wondering how so many people could be here taking part and seeming to take such delight in such a hastily conceived idea. It seemed new for everyone who was there and it was certainly new for us. When it hit you the sound of the brass wasn’t that different to amplifier cabs at full blast…”

The night ended with standing ovations, while the press reaction was encouraging.

“British Sea Power usually sound bigger than their six members as it is – let alone when they throw a brass band into the mix… beautiful… exultant…” – The Independent.

“Wondrous… bold and triumphant… there’s a breathtaking poetic beauty coursing through Sea Of Brass” – The Quietus

But maybe the most most telling review of the Sea Of Brass shows came from the last of the sequence – from Derby Theatre where BSP finally got to play alongside Derwent Brass. The review appeared on the brass-bands website 4barsrest.com. This review felt particularly pleasing because it came from someone within the brass milieu, and also because of the review’s no-holds-barred conclusion.

‘“The most moving moment came at the start of the encore,” wrote Elliott Davies. “Waving Flags has always been an uplifting pro-immigration torch song, but with the backing of the brass, it becomes a life-affirming, forward-thinking, humanist anthem – the perfect antidote to miserable UKIP small-mindedness. Were [Nigel] Farage in the room, I like to think the sheer force of the goodwill would have caused his face to melt like those of the Nazis at the end of Raiders Of The Lost Ark. Any gig capable of conjuring an image of Farage bleeding to death through his punctured eyeballs is surely worthy of the highest praise possible.

The boss bozo of bigotry blasted and broken by brass – figuratively speaking of course… What finer testimony is there? When music can conjure such images then surely useful purpose has been served. Such powers are now, hopefully, also manifest in the recordings of Sea Of Brass – on the audio and visual documentation from the Barbican and on the studio-album version. The latter was recorded with Fodens Band, who in 2012 won a rare brass-band double, being crowned both British Open champions and National Champions of Great Britain. Here is music of alliance, solidarity and concord – music made by all kinds of people, made by people acting in a spirit of universality over division. We hope you enjoy it.

*Sleevenotes by Roy Wilkinson, author of the British Sea Power-themed rock/family/forestry memoir Do It For Your Mum www.doitforyourmum.com)

‘The best band in Britain’ – The Sunday Times.

‘British Sea Power’s slightly camp, wholly menacing and startlingly audacious debut is unlike anything else’ – The Guardian.

‘Out of this world… The track Carrion is truly wondrous, the crowning moment of a dazzling debut’ – NME.

“One of the most exciting albums of 2003 has arrived… a near hysterical fervour runs through every song’ – The Daily Telegraph.

‘Stadium-sized melodies and exquisite songwriting… The intelligent, nonconformist listener has a new band to love’ – MOJO.

‘This always poised, often epic rock oscillates between the frenzied and the elegiac. A strange and exhilarating record’ – The Independent on Sunday